Once upon a time, women were considered too fragile to play the game of basketball as we know it. Instead of running up and down the length of the court, they were consigned to one end or the other, lest their supposedly delicate constitutions be upset.

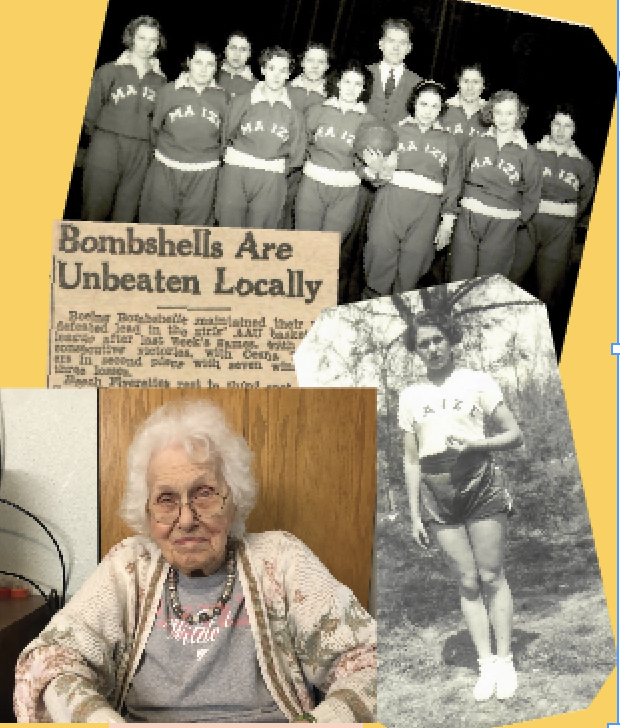

Except somebody forgot to tell Ruth Ott Gregory. During World War II, she was one of a number of Wichita-area women who played the game the way it’s played today, entertaining sports-starved crowds and sometimes beating high school boys teams in the process.

Gregory, who turned 100 last month, enjoys recalling those days.

“Lord yes, I’d still be playing if I could,” she said when asked if she misses basketball. “Nothing like it.”

Gregory grew up as Ruth Ott on a farm outside of what’s now Maize. Her father nailed a basket to the barn, which is where Ruth honed her specialty, shooting. A member of the first girls’ basketball team at Maize High School, she attended Kansas State University for a year before she was forced to return home when her father died.

Her former high school coach, Buddy Reynolds, had started coaching women’s teams sponsored by local companies, and Ruth joined. Over several years she played for Boeing, Thurston (a large clothing store) and Steffen’s (now Highland Dairy). Gregory remembers her old coach as tough but fair. “You had to work hard or you would be dumped,” she said. “That Buddy Reynolds was excellent.”

In those days, the rules for women’s basketball called for six-on-six games, rather than five-on-five as boys and men played. Three females from each team were assigned to each end of the floor, providing offense and defense respectively, and were permitted only to pass the ball across the center line.

The women’s games were popular, as can be seen by articles in the Wichita Eagle and Wichita Beacon. One article referred to the “famous” and “powerful” Thurstons, while another noted that the Boeing Bombshells were undefeated through the first eight games of their season. Other squads included the Cessna Trainers and Beechcraft Flyerettes and Culver Cadets. Teams from as far away as Des Moines and Michigan also came through town for games.

Gregory, a five-foot-six guard, was described as one of the stars of the Boeing Bombshells, along with Coach Reynolds’ wife, Hazel, and Corene Smith, who was known as one of the best players in the country. Games were often played at the old Forum, predecessor of Century II, sometimes to raise money for causes such as the fight against infantile paralysis.

Gregory took part in what was billed as the first game ever played between girls and boys teams at the Forum, a contest between the Thurston women and Norwich High School team. The “classy” Thurston team won 19-18, repeating the feat in a rematch held in Norwich, according to a newspaper report. In a game held in Arkansas City to raise money for recreational facilities, they lost to a team made up of “refinery boys.” A newspaper article said they “have had no opposition here among girls’ teams and have had to play boys’ teams.” Gregory once played in a double-header with the Harlem Globetrotters at the Forum, meeting that team’s legendary founder, Abe Saperstein.

The Thurston team ran into trouble with the AAU (American Athletic Union) for traveling to Canada to play a series of games under boys’ rules against the Edmonton Grads, probably the best and best-known women’s team in North America. That left them unable to play in the AAU national tourney, “which they probably could have won,” according to one newspaper article.

The Edmonton games were held to raise money for the “Milk-for-Britain” fund that benefited children in war-stricken England. An Edmonton newspaper article called the Thurston team “one of the strongest” and best-known in the United States. Most of the players worked in Wichita’s aircraft plants, and an article noted that they were “sacrificing both wages and time in order to make this series possible.” On at least five occasions, the Thurston players pooled their gas ration stamps and made the 1,600-mile drive to and from Edmonton.

Reynolds was quoted as saying the AAU ban “isn’t worrying us much. The organization doesn’t give a hoot about girls’ basketball because it doesn’t make any money from it whereas it makes $15,000 or more from a national men’s tourney.”

The Wichita teams’ insistence on playing basketball by men’s rules didn’t change the women’s game overnight. Some high schools continued playing six-on-six basketball into the 1990s. (It survives today in the “Granny Basketball League”). However, commentators such as legendary University of Tennessee coach Pat Summitt have given teams like the Thurstons credit for paving the way.

“Several people have commented that she was one of those who was instrumental in laying the foundation for women’s basketball as we know it today, which in my book is pretty awesome,” Gregory’s daughter, Ruth Feather, said.

Feather believes her mother is the last surviving member of those Wichita teams.

After her basketball career, Gregory worked for Sedgwick County and moved several times with her husband, Gene, a manager for Coca-Cola, before returning to Kansas. The couple raised three son and two daughters, and Feather said family get-togethers often included her mom taking part in shooting contests. “Mom would always put my dad out,” Feather said. “He couldn’t compete with her.”

Ruth kept up with the evolution of women’s basketball, which included later pioneers such as Wichita native Lynette Woodard joining the Harlem Globetrotters. “She saw the changes and she loved every minute of it,” Feather said.

She also had a few favorites among male players. “Larry Bird, if I heard his name one more time again, I thought I was going to throw up,” Feather joked of her mother’ fondness for the Boston Celtics great.

Often while watching games on TV, Gregory will remark that “when somebody’s not making free throws, that’s what loses game.”

Want to get on her bad side? “Mention that you’re a KU fan,”

Feather said. “She’s very adamant about K-State.”

When a visitor to Gregory’s apartment did just that, Gregory shook her head and said: “Who’s KU?”

Gregory moved to LakePoint’s assisted living facility in Wichita in 2013. Last year, before its first girls’ basketball game of the season, Maize High honored her with flowers and a standing ovation for her contributions to the sport as well as being the oldest surviving graduate (class of ’36).

“The place was packed,” Feather said. “My son wheeled her out. When she was introduced, there wasn’t a dry eye in the house.”

One great-granddaughter, Mallory Feather, plays softball and tennis at Valley Center, and another, Jillian Gregory, plays volleyball at a Maize middle school. Three more great grandchildren- Kylan, Kersey and Kinley Gregory- play basketball in Wellington, and another great- Katie Waller- is a horsewoman in Nashville, TN.

Feather said her mother asked her one time: “Would you think I was a terrible person if I told you that the years when I played basketball were the best years of my life?”

Then there was the time, not too long ago, when Gregory crumpled up a tissue box and tossed it into a trash can across the room.

“She turned around and looked at me and said ‘I still have it,’” Feather said. “She’s a character.”