ARKANSAS CITY — An early Great Plains civilization centered around the Arkansas River was much bigger and more influential than previously thought, says a Wichita State professor of anthropology.

Don Blakeslee, who’s been conducting archaeological research here for a decade, said recent discoveries challenge the view of the Plains as being sparsley populated and less culturally advanced than other pre-Columbian societies.

In 2017, Blakeslee claimed to have confirmed the location of an ancient Native American settlement known as Etzanoa in a spot near Arkansas City where it had long been suspected.

Now, Blakeslee says Etzanoa was part of a nation called Quivira that totalled more than 200,000 people. Ancestors of today’s Wichita tribe, they traded goods across North America and even had a previously unknown common language, he says.

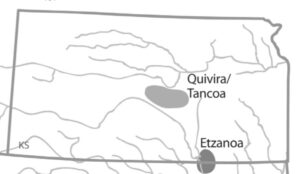

Map shows likely spots where Francisco Coronado reached Quivira in 1541 (its people called themselves Tancoa) and Juan de Ornate found Etzanoa 60 years later.

Source: Kansas Historical Society

“It’s going to revolutionize our view of the Great Plains societies, and it already has for me and my students,” Blakeslee said in a news release from the school. “Charles Mann wrote (in the book) ‘1491’ about the thriving Native American societies before the time of Columbus in South America, Central America and the American Southeast, but when he talked about the Great Plains, he called them distant and sparsely populated and occupied by hunters and gatherers. No. In its day, Quivira was probably the most important native political unit in what’s now the United States.”

The people who created Quivira are believed to have arrived in Kansas in the late 1300s, and Quivira was fully formed around 1450. The archaeological evidence shows that they grew crops and also hunted bison in huge numbers. Over 80 percent of the chipped-stone artifacts from the town of Etzanoa are specialized for processing bison products, and documentary evidence shows that these products were exported from coast to coast.

Quivira was visited by two Spanish expeditions that left records, led by Francisco Coronado (1541) and Juan de Onate (1601). By the time of the first French visit in 1719, the nation was already in a steep decline.

Blakeslee’s findings — which he presented at the annual Society for American Archaeology meeting March 30-April 2 in Portland — focus on three types of evidence discovered about Etzanoa and Quivira: documentary evidence, linguistic evidence and the archaeological evidence.

Documentary evidence

Blakeslee estimates the population of Quivira to have been roughly 200,000. This number is extrapolated from Blakeslee’s estimate of Etzanoa having a population of 17,000 to over 20,000 people and the presence of 10 or more large towns elsewhere in Quivira. Those numbers are at the high end of estimates made by other researchers. The town of Etzanoa was originally listed as 22 separate sites.

When recorded more accurately as a connected society of large towns rather than unrelated villages, Blakeslee says, it’s clear that Quivira was much more organized and far-reaching than anyone had previously thought.

The Quiviran people had hereditary chiefs, priests, interpreters and ambassadors they would send to neighboring nations, Blakeslee said.

“They were an organized society, one far different from the Hollywood version,” Blakeslee said. “But they have not been given any recognition at all in American history books.”

Linguistic evidence

Evidence in documents from the earliest expeditions to the southwest of the continent shows that some people in Quivira could speak Nahuatl, the language of the Aztec empire. Additionally, Blakeslee has accumulated evidence showing that Nahuatl was the basis for a Lingua Franca, a shared language between speakers of differing native languages, that was in use from Galveston Island in Texas to California, and from Kansas deep into Mexico in pre-historic times. He calls it the first clear documentation of a pre-historic native Lingua Franca in North America.

Archaeological evidence

Blakeslee believes the land area of Quivira was at least as large as the Republic of Ireland, with the currently documented borders being from the Kansas River in the north; the town of Larned, Kansas in the west; east into Missouri; and south into Oklahoma.

Documents from the DeSoto expedition of 1539-1542 indicate large quantities of Quiviran bison products as far east as Florida, Georgia and South Carolina, including meat, robes and war gear such as rawhide shields, helmets and body armor. At the same time, other expeditions documented bison rawhide shields in use on the west coast of Mexico and along the Colorado River between Arizona and California. Tobacco pipes made by Quivirans have been found in sites created by the Apache, Pawnee, Missouria and Caddo tribes and in the pueblos of Pecos and Taos.

The people of Quivira received various items in return. The items that traveled the farthest are pieces of obsidian from central Mexico and Jalisco, far down the west coast. Student experience

Blakeslee has taught at WSU since 1976. Wichita State students working on this research with him are receiving a hands-on learning experience.

Kait Carter is a WSU graduate student majoring in anthropology who has found a passion in uncovering and illuminating the history of the site.

“There’s so much knowledge out there that could be acquired, and just reconstructing history is extremely interesting,” Carter said.