When Robert Weems Jr. joined the faculty of the Wichita State history department in 2011, one of his first research projects was to document some of the city’s black entrepreneurs and their businesses.

People like the Rev. John Henry Van Leu who at the turn of the century was one of the largest landowners in Wichita. Van Leu owned a department store and an office building on North Main that housed several early Black-owned businesses in Wichita including Jackson Mortuary.

As part of a series of Black History Month presentations at the Advanced Learning Library, Weems — who is the Willard Garvey Distinguished Professor of Business History at WSU — shared insights into his Wichita African American Business History Project. A video recording of the presentation can be found on the Wichita Public Library’s YouTube channel (youtube.com/c/wichitalibraryorg).

“Wichita blacks, like their counterparts throughout the country, prioritized business development during the 1920s, which has been called a golden age of African American business formation,” Weems said.

Compared to major cities such as Chicago, Wichita’s black population was relatively small, numbering little more than 3,500 in 1920. So that meant there weren’t large commercial businesses like black insurance companies or banks, said Weems.

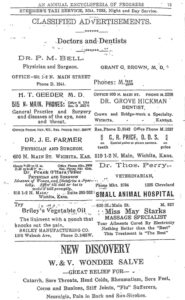

But there were black-owned businesses such as photographers, funeral homes, architects and lighting and department stores, Weems noted, as he showed an image of the cover of the Wichita Negro Year Book 1922-1923, a community directory.

Sexton Tailoring was one of those businesses, he pointed out. It was owned by Edwin Sexton, whose son, Linwood, went on to become a celebrated hometown football player for the WSU Shockers.

One motivation for Weems’ research is what he calls the “sad reality” that the history of black businesses may be lost forever. So, he’s doing his part to help change that. He’s written five books in the African American business genre and was an adviser and appeared in the 2019 PBS documentary, “Boss: The Black Experience in Business.”

“Even before coming to Wichita, I developed the idea of an oral history project chronicling the history of African American entrepreneurship in a particular setting. Where I worked previously, the University of Missouri-Columbia, wasn’t really conducive to such a project because there was a rather small African American business presence in Columbia. Wichita, conversely, had an African American business presence that was feasible for what I wanted to do,” Weems said after his presentation.

Between 2011 and 2014, Weems conducted a series of interviews with owners and descendants of black-owned businesses in Wichita. He also interviewed longtime residents to get a sense of the community and the importance of those businesses.

The resulting 32 audio recordings and other project documentation were donated to WSU’s special collections department at Ablah Library in 2017. The recordings can be accessed online: go to archivesspace.wichita.edu and search for the project.

“History is about documentation, so if the records are gone and the buildings are demolished, it’s gone,” Weems said.

Among those he interviewed for the Wichita Black business history project were George Johnson, grandson of Van Leu; “Rip” Gooch, whose Aero Services Inc. was a pioneering fixed-based operation; Charles F. McAfee, a world-renowned architect based in Wichita; Anderson “Gene” Jackson, whose grandfather Abner B. Jackson Sr. started Jackson Mortuary in 1926; Denise Sherman, the current head of The Kansas African American Museum whose father, Dr. Othello Curry, ran a vet practice; and Frankie Howard Mason, whose mother, Xavia Hightower Howard, was the second-generation owner of Citizens Funeral Home and the first African American woman in Kansas to hold a dual license as a funeral director and embalmer.

In the early 20th century, most black-owned businesses were located on North Main. But by the 1940s, the hub of black businesses had moved to the Ninth and Cleveland area. One landmark of that area that remains is the Dunbar Theatre, which opened in 1941 and became not only a movie house but also a meeting place, Weems said. The construction of I-135 eventually cut through much of that community.

African American churches played what Weems called a prominent role in supporting and getting the word out about black businesses.

But folks in the community also did their part, according to some current and former residents of the area who attended the presentation.

“We talked to each other, and it was word of mouth,” said 79-year-old Ann Washington. “Back in the day, we all lived along there, and we just knew everybody.”

With Wichita being fairly isolated geographically and having a smaller black population than some urban areas, there seems to have been a stronger impulse to create a sense of village and community support here, Weems said.

Black businesses sometimes had trouble getting access to capital, Weems noted. He found it fascinating that Jackson Mortuary helped fund some early African American enterprises that had been turned down by local banks. Some of those discriminatory practices continued as late as the 1980s, Weems noted, when black oilman Henry Wofford couldn’t get local funding for his independent oil company and had to go to Tulsa for loans.

While his 2011-14 project wasn’t a definitive history of Wichita’s black-owned businesses, Weems said, he hopes his project inspires other to document history. As a consequence of the project, Weems said, the Heartland Black Chamber of Commerce created the Wichita Black Business Hall of Fame in 2016.

Contact Amy Geiszler-Jones at algj64@sbcglobal.net.