Eighty years ago this spring, the Little Arkansas River spilled out of its banks in a way that spelled big trouble. Swollen by heavy rain, the river and nearby Chisholm Creek drove an estimated 5,000 Wichitans from their homes, washed out bridges and covered much of downtown.

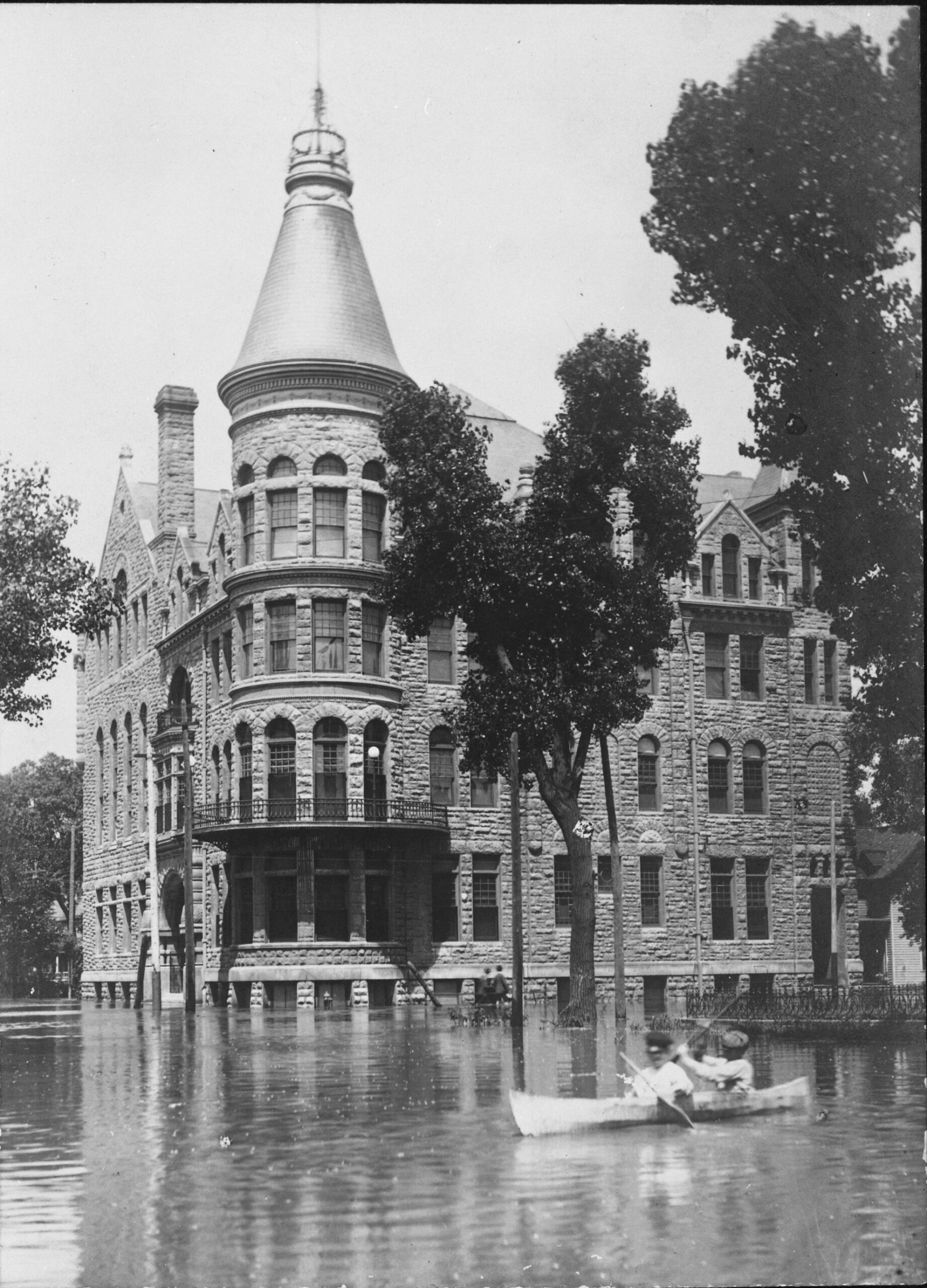

In Riverside Park, the historic Park Villa building was surrounded by acres of water four feet deep. In the stockyards along 21st, workers loaded 4,000 hogs onto railroad cars to keep them from drowning. To the north, Valley Center and a swath of Sedgwick County were under water. Flooding was blamed for two drownings and two fatal heart attacks.

The deluge overshadowed news from World War II for a few days, although flooding in Wichita was nothing new. Large areas of the city had been submerged during floods in 1877, 1904, 1916 and 1923. The 1944 flood was only different in that it convinced local leaders that something had to be done, probably because the city had nearly doubled in size during the war years and the potential for damage was so much greater. But the proposed solution — what came to be known as the “Big Ditch” — was controversial.

Flood plain pains

The central part of Wichita, from Hillside to Ridge, sits in a flood plain watered by the Arkansas River, Little Arkansas River and their tributaries. Historically, the Little Arkansas and multiforked Chisholm Creek presented a more persistent flood threat than the larger Arkansas River. “Those are flashy streams — they’ll come up and down rather quickly,” said Scott Lindebak, stormwater manager for Sedgwick County.

In 1904, the city tried removing obstructions from Chisholm Creek to improve its flow; a few years later, part of the creek was turned into the forerunner of the paved drainage canal that now runs through the city under I-135. “A lot of people thought flooding was solved when the early version of the canal was built, but that proved wrong when downtown flooded,” Lindebak said.

Between 1926 and 1928, the city spent more than $1 million straightening and deepening the creek and building dikes along the banks of the Little Arkansas. But a 1935 survey by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers found several problems with these works, including low bridges along the river that acted as dams during periods of high water.

To prevent future flooding, the Corps proposed what would be one of the largest water diversion projects in U.S. history if completed.

The project would start by diverting the west and north forks of Chisholm Creek into the Little Arkansas at 37th Street. To handle overflow, a ditch would be built to the southwest, connecting with the Arkansas River near 21st and West. To handle overflow from that point, a shallow depression known as the Big Slough would be enlarged around the west side of the city. This floodway (also connected to Cowskin and Big Slough creeks) would stretch 18 miles, passing through Haysville before reconnecting with the Arkansas near Derby. A separate floodway would run from the Little Arkansas west of Valley Center to the Arkansas about 10 miles above Wichita.

The Corps’ report concluded that “construction of Big Slough floodway is practically a necessity for the ultimate protection of Wichita.”

But when hearings on the Corps’ plan were held in Wichita in 1936, local officials and farmers who owned land in the Big Slough were opposed. Officials said the city and county couldn’t afford their portion of the project. Farmers didn’t want to give up 6,600 acres of prime farmland for a “big ditch” only needed on an irregular basis. Some taxpayers wondered why they should foot the bill for people rash enough to build in a flood plain.

However, the 1944 flood waters had barely subsided when the Wichita Eagle reported that support for the Corps plan “is growing daily.” Lobbying by the Wichita Chamber of Commerce helped persuade Congress to authorize federal funding for the Big Slough project in 1945. The Kansas State Supreme Court decided in 1949 that the project could proceed, although that didn’t eliminate all opposition. Some landowners tried to keep surveyors off their property, and one farmer allegedly took a pot shot at a worker.

Excavation began in 1950. In all, the design called for 40 miles of channel excavation and 97 miles of levees. The Big Slough portion ranges from 500 to 900 feet in width and can carry twice as much water as the Arkansas River. Delayed in part by the Korean War, the project was finished in 1959 at a cost of $20 million, with the federal government providing $13 million, the city and county $3 million each, and the state $1 million. Initially known as the Wichita and Valley Center Flood Control Project, its name was changed in 2019 to the MS Mitchell Floodway, in honor of a city engineer who played a key role in its development — M.S. “Big Ditch Mitch” Mitchell.

Today, officials say, the project protects some $7 billion in property and has prevented major floods on 10 occasions since completion. The water we see in it most of the time is from rain, the ground and local drainage, not the rivers, but the floodway is available when needed.

“It’s a pretty cool system when you think about it,” Lindebak said. “This system has definitely elevated the city’s commerce and viability — not having the different floods that were disrupting the city’s life.”

Recreational use?

Other potentially beneficial uses of the Big Ditch have not come to fruition. In 1970, for instance, the Wichita-Sedgwick County Planning Department broached the idea of using it for water sports, bird watching, walking and bicycling trails and other recreational purposes. A dam and fishing pond at 21st Street would provide convenient recreation as well as scenic interest. A nature park at the juncture of the Arkansas River and floodway could highlight the ecology of the region. The floodway could become “a linear unifying element providing scenic beauty and providing recreation for Sedgwick County residents as well as being an impressive feature for visitors to the City.” It and a similar 1976 plan went nowhere.

In 2016, the Wichita Bicycle and Pedestrian Advisory Board again advocated for trails along the Big Ditch. An advisory board member noted that he’d bicycled trails built along levees in several other Kansas cities.

David Dennis, the Sedgwick County commissioner who has represented western Sedgwick County for the past seven years, said he knows some residents would like to see the Big Ditch utilized for more. In his opinion, potential problems outweigh any upside. Maintenance costs — now about $1 million a year, split between the city and county — would certainly go up if the levees along the project handled bicycle and foot traffic, he said. The property was originally condemned for flood control; if the city and county tried to use it for something else, its original owners could try to get their land back. If the Corps of Engineers objected and decertified it for flood control, many property owners in the county would have to buy flood insurance, Dennis said.

“So it’s not something we take lightly,” he said. “They put it together for flood control, and that’s what we have to use it for.”

West Wichita long ago leapfrogged the Big Ditch and has continued to grow. Today, the Big Ditch divides it from the rest of the city — a not particularly attractive green and brown expanse (when there’s no water in it) viewed only from bridges and highways. For now, it appears the Big Ditch will remain only that.

Editor’s note: “The Big Ditch: The Wichita-Valley Center Flood Control Project” by David Guilliams (1998, Fairmount Folio), was a primary source for this article.