Three months before her death, Clara Schmidt asked her daughter to write a book about the family’s story.

There was no shortage of material.

Schmidt, a nurse from Newton, and her husband, John, a physician from Goessel, led a sometimes precarious existence as medical missionaries in Paraguay — and took their children along for the ride.

“They were driven by their set of beliefs as well as their love of adventure,” the Schmidts’ daughter, Marlene Fiol, said.

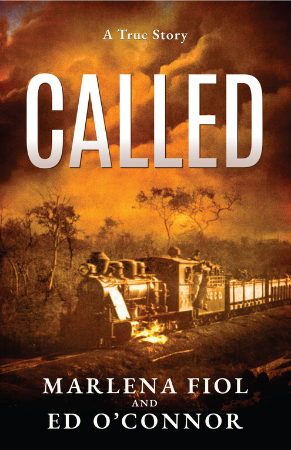

Fiol and her husband, Ed O’Connor, tell her parents’ tale in “Called,” which was published last year and is available on Amazon.

The story begins with John Schmidt, then a new doctor, enroute to Paraguay in June of 1941 as a medical missionary to the Fernheim Mennonite Colony, whose members had left Russia to escape Communism. The group first went to Germany, then to Paraguay through the Mennonite Central Committee.

Schmidt encountered challenges even though he had grown up in a Mennonite farm family speaking the same Low-German dialect as his patients. His medical textbooks and instruments arrived — damaged — months after he did. Many colonists were pro-Hitler since Germany had taken them in, and there were deep tensions with the smaller anti-Nazi fraction.

John met Clara Regier a day before leaving for Paraguay, introduced by his older brother Herb, a Newton surgeon. Clara was a nursing student who had earlier graduated from Bethel College. They courted mainly through letters before marrying in the summer 1943. The newlyweds left for Paraguay, where Clara worked with her husband and set up a nursing program.

John Schmidt’s bleeding ulcer spurred their return to the United States several years later. John established a medical practice and the started a family. Then in 1951, the Mennonite Central Committee asked him to build and staff a leprosy colony in east Paraguay.

Schmidt was appalled by how the disease was being treated, with patients basically imprisoned in institutions. He believed they should be treated in their homes if possible, use a then-new drug called Dapsone to help them and often rode a hose in the back country in search of patients.

The Schmidts faced suspicion and opposition from local residents, the American Leprosy Mission and sometimes the MCC. When a group of Paraguayan men threatened to kill Clara at the site of a new clinic, she disarmed them by inviting them for refreshments and briefly praying. “She always held that as an example of God’s protection and God’s grace in their lives,” Fiol said.

The book also describes the family’s 1960 three-month journey from Paraguay to Kansas. John bought a small Volvo station wagon for his family of eight. The Pan American Highway was often little more than a rutted path through treacherous mountain passes in South America. Clara and the older children frequently pushed the Volvo uphill in the Andes. There were 38 rivers to cross in Costa Rica and no bridges along its newly constructed highway. If a raft was unavailable John asked the drivers of bulldozers and trucks to pull the Volvo across.

The Schmidts moved to Goessel in 1983, then returned to Paraguay in the late 1980s to care for the elderly in the Menno Mennonite Colony. The couple died in Paraguay, John in 2003 and Clara in 2010.

Fiol and O’Connor are retired business professors and live in Eugene, Ore. Fiol spent part of her childhood in Newton, began college at Bethel and also took classes at Wichita State University.

Fiol and O’Connor poured through boxes of diaries, journals, letters and more that were given to them by Clara Schmidt before her death, reviewed materials provided by the MCC and interviewed people who knew the couple.

Contact Nancy Singleton at ncsingleton@att.net.