Charles McAfee understands the anger that’s driving young Wichita protesters to rally against racial disparity and police misconduct. He felt it 70 years ago as a talented young athlete denied the opportunity to compete in certain sports because he was black. He felt it as a Korean War veteran demanding to be treated like other university architectural students. He felt it for decades as he established himself as a nationally known architect and fought for political and socioeconomic changes here.

Keeping himself home recently because of the coronavirus pandemic, McAfee, now 86, follows events and remembers.

“It’s allowed me to go back and spend a lot of time reliving some of those years,” he said, “and I keep hearing everybody say the only way we get anything done is to go the streets, and they’re basically right.”

McAfee is part of earlier generations of black activists who say they support the current protests. They are optimistic or at least hopeful that the fight they’ve waged so long is making progress, despite the glaring disparities that remain. It’s easy for them to relate to young protesters because they each experienced and stood up to discrimination.

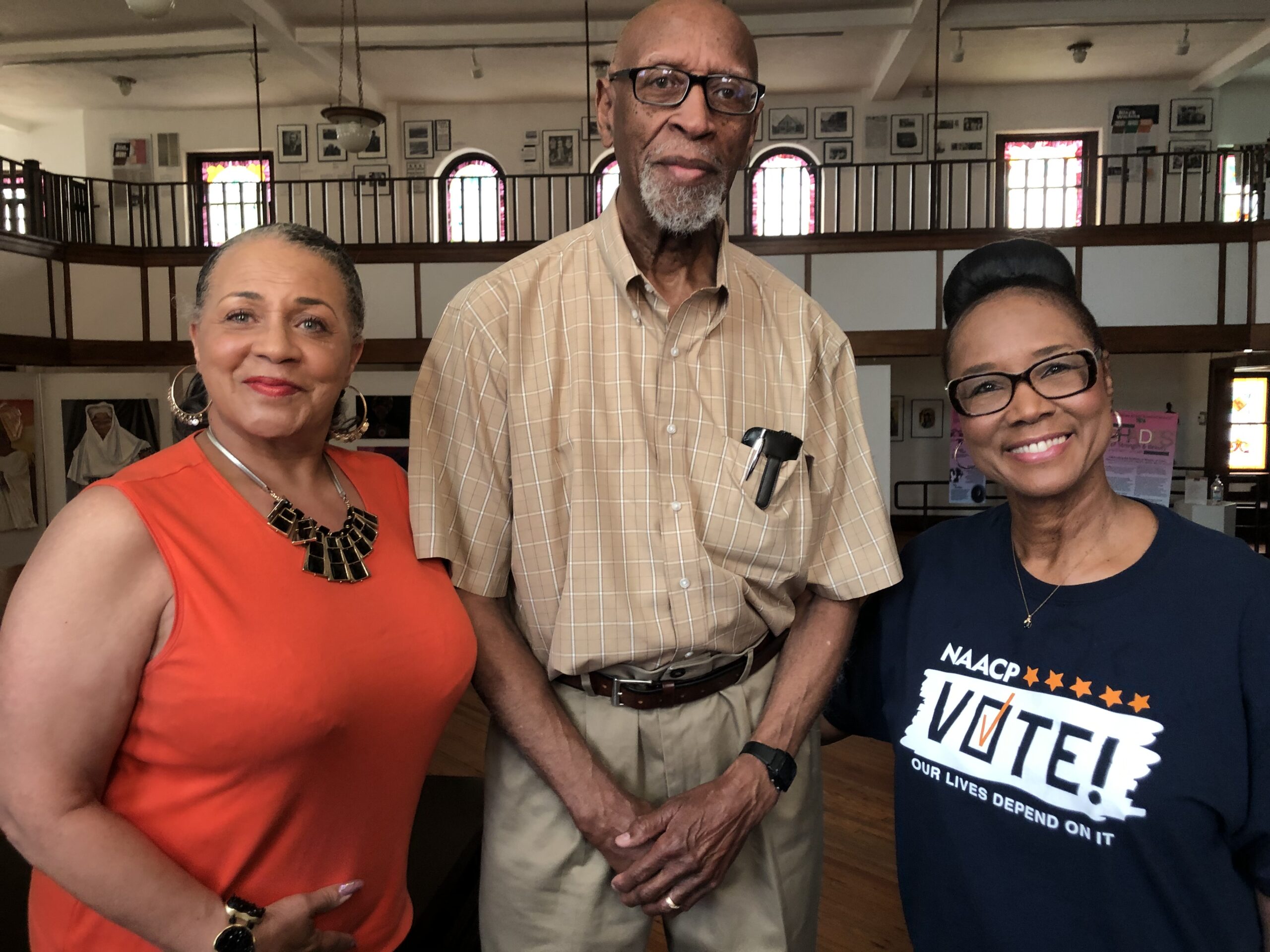

“I think it’s wonderful, I think it’s long overdue, and I believe it is now affecting our whole country and the whole country is rising up,” said Sheila Kinnard, a recently retired educator whose mother, Jo Brown, was the first woman of color elected to the Wichita school board. “It’s not just a black protest, it’s a multi-cultural protest. We have young people who say it’s been too long.”

Kinnard’s father is Dr. Val Brown, Sr., one of two physicians who treated most black Wichitans during the 1950s. Despite his education and profession, though, the Browns weren’t welcome to eat in certain Wichita restaurants. When he took his family on vacation, he booked them in segregated hotels, consulting “The Negro Motorist Green-Book.”

“Mom didn’t even know he was using it until we found out later,” Kinnard said, adding that she “learned to go to the bathroom in a field” rather than use the facilities in white-owned restaurants when they were traveling.

Over time, Dr. Brown was eventually able to see his patients in integrated hospital wards, and Kinnard was in the first class of black middle school students to attend school with white classmates. When her mother was elected to the school board she pushed for additional black teachers and more.

“She wanted to have administrators and counselors of color in every school,” Kinnard said. Kinnard, who retired as drama teacher at Mayberry Middle School, said the district today “is just not filling the well with minority teachers like they did. That’s systematic. There’s no one there that’s waving the flag for that.”

Kinnard said she went through “kind of a sad period” after the death of George Floyd, the black man whose killing by police in Minneapolis sparked the recent protests, but she’s become hopeful as the movement appears to be sustaining momentum. She does not favor “defunding” police everywhere, as some advocate, but wants to “reallocate some of the money that’s going to policing” into more productive channels.

McAfee’s family was settled here in 1865 – before Wichita was even a city – by his great-grandfather, who was wounded while fighting for the Union during the Civil War. Nevertheless, when it came to participating in organized sports, McAfee ran into unofficial racial quotas, and when it was time to choose a college, his parents sent him to the University of Nebraska “because both KU and K-State were very segregated.”

Invited to join the Nebraska basketball team by its coach, McAfee had his college years interrupted by serving in the Korean War. Returning to Nebraska with his wife, a graduate of Howard University in Washington, D.C., McAfee discovered that some landlords would not rent to them, and he had to overcome a professor seemingly opposed to his graduating. McAfee started his own architectural firm in Wichita, winning awards and seeing his buildings dot skylines here and elsewhere. Yet for every successful bid, he encountered other situations where the white power structure in the form of the city’s banks and biggest businessmen treated him differently. When he tried to buy a house on the GI Bill, “the Veterans Administration turned me down because it was too far east, almost to Hillside.” When he finally did build a house in a neighborhood considered off-limits to blacks, somebody fired two shots into it during the night as his daughter lay inside. By then, he’d been president of the Urban League and National Conference of Christians and Jews and served on numerous United Fund boards. “I’m trying to prove to this town that ‘we’re okay.’ It didn’t mean a damn thing.”

McAfee spent “80 percent of his time” on efforts like helping black attorney A. Price Woodard get elected to the City Council and Jo Brown to the school board. During those battles, McAfee said, “I was accused of playing the ‘race card.’ So when you see people demonstrate in the street, it’s because people like me, with all the education we were supposed to need, and all the talent I did have, my common sense and conversation couldn’t change one out of 10 white folks’ belief in anything.”

McAfee said it’s no coincidence that his two daughters, who are both architects, chose to continue the firm’s work in Atlanta and Dallas rather than here.

Galyn Vesey took part in the best-known civil rights action in Wichita’s history – 1958 the Dockum Drugstore sit-in that desegregated the Rexall chain’s lunch counters. At the time, he was attending what was then Wichita University. Vesey had already quietly protested segregation practices while working as a dishwasher at Kress, another downtown store with a lunch counter. Vesey ate the free doughnuts employees got two or three times in its whites-only area before his boss told him to cut it out. When young members of the NAACP proposed the Dockum sit-in, Vesey was on board.

“There are times when you need a crowd, and times where an individual needs to step up,” he said.

Vesey went on to work in the mayor’s office, Urban League, health and welfare agencies, then eventually further study and teaching at Syracuse University and the University of Oklahoma before returning to Wichita. As he researches the city’s black history for a book he plans to write, Vesey predicts current protesters “are going to make a difference, these young people, just like they did in ’58.”

In almost the same breath, though, he says, “Yeah, we’ve made some progress, but there are things not dealt with.”

Policing practices and housing discrimination are two areas that come to mind for him, but the real change he believes is needed goes much deeper.

“When you talk about human beings, we need to get over this thing about race. There is no race. There is the human race. God knows what he was doing.”

Former City Councilwoman Lavonta Williams said she wasn’t involved in civil right issues growing up in Wichita “but I should have been.” She remembers what happened when she applied to be a teacher in USD 259, after graduating from Emporia State University.

“I was straight out of college and I had one of the hugest afros. I remember going to one of the principals to apply and the only thing I remember him asking me was ‘Do you always wear your hair that way?’”

Williams spent 35 years teaching middle school. After being asked to join the advisory board for her district’s City Councilman, Carl Brewer, she was appointed to fill his seat in 2007 and then won election on her own two years later, becoming the first African American woman to serve as vice mayor. Williams often battled for her constituents on issues like recreational facilities and utility bills and has stayed active since being term-limited in activities such as incouraging voting and a coronavirus response coalition.

She’s a fan of both the young protesters and of Wichita Police Chief Gordon Ramsay. She doesn’t condone violence that accompanied a protest at 21st and Amidon, but points to the peaceful demonstration at 13th and Oliver days later.

“There was a huge group, they basically took over that intersection, and the police allowed them to protest,” Williams said. “That’s the kind of chief we have.”

Williams believes there’s an “opening of dialogue” underway. Still, she’s realistic.

“This is 50 years later, we’re still fighting the same thing.”