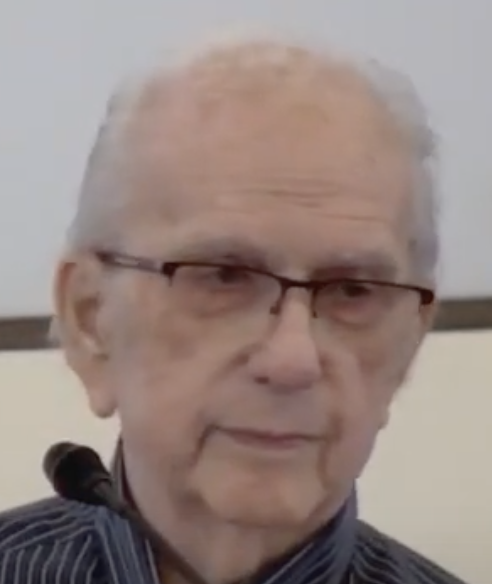

For Ted Blankenship, this time it’s serious.

Blankenship, who started writing his “It’s Not Serious” column 67 years ago, says he may have filed his last one. Blankenship cited a combination of health problems and an uncooperative new computer for his decision.

Then again, he’s not ruling out a return.

“It’s Not Serious” has been a staple of The Active Age since 2012. Blankenship started it in 1957 while working for the Hutchinson News and later continued it for newspapers in Coffeyville and Wichita.

“I enjoyed every one of them,” he said during an interview last month.

If Blankenship has written his last column, it caps what surely must be one of the longest journalism careers in Kansas, if not the United States. Many readers probably feel like they already know him since he often wrote about his life — from being a short, chubby kid to having various adventures with people, animals, vehicles, musical instruments and more.

Blankenship grew up in the oil fields of Teeterville, now a ghost town in the Flint Hills, and initially planned to be a petroleum engineer like his father. As a teenager, he played trumpet and sang professionally on a radio station in Coffeyville. He went into the U.S. Air Force as a musician during the Korean War but got reassigned as a typist when superiors discovered he had two years of college and could type.

After the war, he earned a journalism degree from the University of Kansas and interned at the Topeka Capital newspaper, which eventually hired him in the mid-1950s.

“The editor called me in and said, ‘Did you ever live on a farm?’ I said no. He said, ‘Do you know anything about farming at all?’ I said no. He said, ‘Well, you’re our new farm writer.’”

Blankenship quit that job not long after the Capital merged with the rival Topeka Journal, worked for a trade magazine for a year, then moved to the Hutchinson News as a general assignment reporter. After a car accident one day, Blankenship wrote a column about the cumbersome neck brace he was wearing as a result, illustrated with a picture of African neck rings (it was a different time).

The column caught on, and Blankenship kept it going in Coffeyville and Wichita. Not that he didn’t cover plenty of serious news as well.

In Coffeyville, Blankenship wrote editorials about racial issues.

“I had the whole town on my rear. I had people threaten me on the phone, threaten my kids. It got pretty hairy for a while.”

In 1966, the Wichita Eagle and Beacon hired him to run its Capitol bureau in Topeka during the administration of Gov. Robert Docking (who, as Ted noted in one column from that period, was as vertically challenged as himself). He covered political stories daily, but the most dramatic event of that period was the June 8, 1966, tornado that killed 17 people and leveled a 15-mile swath of the capital. “What a mess it was,” he said. “First time I ever had to show a press card in my life because they had a lot of looters.”

The Eagle and Beacon ran his photograph of some of the damage across the top of its front page.

He returned to Wichita and filled several roles at the paper, from editorial writer to covering the science and energy beats. One assignment took him to Venezuela to cover that country’s nascent oil business.

“I spent an evening with the president of the country, which was interesting. They had AK47s everywhere.”

Blankenship’s son, Tedd, a former art teacher at Southeast High, said his father sometimes dragged him along on assignments to destinations such as an archaeological dig in Oklahoma and nuclear collider in Colorado.

“The joke in the family is that no matter what you say, he’ll say, ‘I wrote a story about that one time.’ And the truth of the matter is, he probably did.”

One series of columns he wrote played a major role in launching the Wichita Jazz Festival, started in 1972 and still going strong today. Blankenship contends he gave up on performing music himself after the Air Force, but he’s been known to pull out his trumpet or pick up a microphone on occasion.

Blankenship taught journalism at Wichita State while working for the Eagle and Beacon, then moved to a job as publications director and journalism teacher at Friends University in 1989. He also spent four years as editor of The Kansas Times magazine. Blankenship was recruited to join the board of The Active Age (then called Active Aging) by Charles Pearson, his former colleague at the Eagle and Beacon. He also wrote a column about photography for this publication, then became its humor columnist after the death of Pearson, who’d been handling that role.

He resigned from the newspaper’s board at the end of 2015.

“He did it reluctantly,” remembers fellow board member Elma Broadfoot. “But he wanted to stay on writing the column because people really liked his column. He cared about the publication, and about seniors. I think that’s why he stayed as long as he did.”

A few years before that, Blankenship and other board members — including Broadfoot, Elvira Crocker and Fran Kentling — stepped in and put out the paper on an emergency basis when its editor at the time became ill. “I really don’t know how we maintained our cool or friendship, but we did,” Broadfoot said.

In 2017, the first five years of Blankenship’s columns for this newspaper were collected in a book, “It’s Not Serious,” with illustrations by former Eagle editorial cartoonist Richard Crowson.

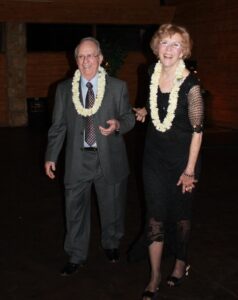

Blankenship and his wife, Dorothy, a native of Texas’ Rio Grande Valley, lived for years in a house built around a silo in Rose Hill, another topic of his columns. Several years ago, they moved to the Catholic Care Center in Bel Aire. In addition to Tedd, the couple have two daughters and one grandchild.

Blankenship was in good spirits during an interview last month, often chuckling as he recounted his life and long career in journalism. He said he appreciates all the many responses from readers his column has generated through the years.

“It was interesting to me that a lot of columns that weren’t intended to be especially funny ended up the ones people liked the most,” he said.

And he left open the possibility of his column returning, if his health and computer cooperate, saying he might write one “whenever I feel like it and I have enough time do it.”