CONCORDIA — At one time, there were 4,000 Germans housed in a P.O.W. camp here. Only one nearly escaped.

We’re at the WWII German P.O.W. Camp Museum just north of Concordia. It’s a rural area of well-tended farm fields, looking much as it did in January 1943 when the U.S. Government bought the land from local farmers. Built in 90 days, the camp included more than 300 buildings, including a hospital, restaurants, a library, a post office, a fire department and barracks. The first trainload of German prisoners arrived in July.

“There was an outdoor recreation area here, surrounded by a barbed wire fence,” our tour guide, Barbara, says. “The prisoners played soccer there. One day, a prisoner laid down in a depression in the ground and covered himself with weeds and grass so he couldn’t be seen. He waited until dark, then crawled through the fence and walked 15 miles up the road to Belleville. He’d somehow obtained a train ticket, but he was a little early. So he went into the cafe to get a cup of coffee while waiting for his train. That coffee was his undoing.”

The waitress brought the coffee to the escapee’s table and said, “That’ll be a nickel.” When the waitress realized he didn’t understand the term nickel, she alerted the sheriff. The escapee was quickly transported back to the Concordia Camp.

“But most of the prisoners didn’t really want to get away from here,” Barbara says. “They were treated well and fed well — probably better than back in wartime Germany. One of the former prisoners wrote us a letter after the war, saying that the time he spent here at Camp Concordia were the best two years of his life.”

The museum, located in one of the camp’s warehouses, is packed with WWII artifacts and memorabilia, including German military uniforms and medals, U.S. Army vehicles and artwork created by some of the prisoners. Barbara is a volunteer tour guide, and her grandfather was one of the local farmers who employed the German prisoners as farmhands.

“Farmers were short-handed during the war because so many local boys were serving in the U.S. military,” she says. “So farmers like my grandfather would call the camp and tell them how many workers they needed for the day. An army truck would bring that many prisoners to the farm in the morning, then pick them up again in the evening.”

The prisoners were paid by the farmers for their work. They got half their pay up front in the form of coupons or script, which they could spend at the camp commissary. Then they were paid the rest in American dollars when they went home.

“One evening, the truck was bringing a load of prisoners back to the camp after a day at the farm. When it stopped at the intersection of Sixth and Lincoln in downtown Concordia, two prisoners just jumped out,” Barbara says. “The guard didn’t notice them missing until he got back to the camp, so he turned around and headed back to get them. He found them walking along the road, heading back to camp on their own. They told him they weren’t trying to get away. They just wanted to stop in town for a cold beer.”

The museum will hold a Victory Day celebration Saturday, May 3 to mark the 80th anniversary of Camp Concordia’s closing and the 10th anniversary of the museum opening.

Otherwise, the museum is open by appointment. Call (785) 243-4303 a couple days in advance to schedule a tour, and Barbara or another volunteer will meet you at the museum. A donation of $5 per person is suggested.

As fascinating as the museum is, Concordia’s best-known attraction is probably the National Orphan Train Complex, dedicated to the preservation of stories and artifacts of those who were part of the Orphan Train Movement from 1854-1929.

The movement began in New York, where thousands of children ended up in orphanages or living on the streets. The Children’s Aid Society founded the Orphan Trains to transport these children to small communities in the Midwest, where they could become part of loving families. Arrangements were made with communities like Concordia.

Mabel Gumersell Erickson, who rode the Orphan Train to Missouri in 1901 at the age of five, later recalled the experience in a letter displayed at the museum.

“With our names pinned to our coats and carrying our own little bundle of ‘worldly belongings,’ we went to live with the ones who had chosen us,” she wrote. “In my bundle, I had a rag doll, a small wooden china man and a tin elephant, which I called Elky. He looked as though he had been stepped on many times. I took these treasures to bed with me every night.”

Mabel’s toys are displayed at the museum. It’s impossible not to be touched by the stories of these children. Some found loving families. But some farmers were just looking for cheap labor. Others had even darker intentions.

A completely restored 1917 Union Pacific Depot is part of the National Orphan Train Complex, as well as an original Orphan Train passenger car. One imagines it filled with children, their faces pressed to the windows as they saw wide-open spaces for the first time.

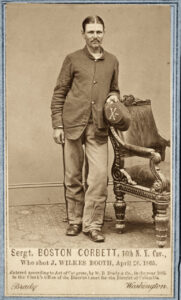

Then there’s a lesser-known Concordia attraction — an obscure spot on the prairie that was once called home by the man who killed John Wilkes Booth.

Thomas H. Corbett was a hat maker known for his eccentric behavior. Historians theorize that his mental issues may have been the result of mercury nitrate fumes he inhaled as part of his profession. Hallucinations and psychosis were common among hat makers back then, hence the expression “mad as a hatter.”

Corbett took to excessive drinking after the deaths of his wife and child but gave it up after meeting a street preacher in Boston. He got sober, changed his first name to Boston and became a street preacher himself.

In 1861, Corbett joined the Union Army. Four years later, in April 1865, his Virginia regiment was sent in pursuit of John Wilkes Booth after the assassination of President Lincoln. The regiment surrounded Booth and one of his accomplices in a Virginia tobacco barn. The soldiers set the barn on fire, attempting to drive Booth from the building and capture him alive. But Boston Corbett saw Booth through a crack in the barn wall and fatally shot him with his Colt revolver.

Many Americans saw Corbett as a national hero. But some saw him as a glory seeker who disobeyed orders. After his discharge, Corbett returned to work as a milliner but was fired from multiple jobs because he’d begun brandishing his pistol at people whom he deemed suspicious. For a while, he toured the country as “Lincoln’s Avenger,” giving lectures about the night John Wilkes Booth was killed.

In 1878, Corbett moved to Concordia, where he acquired a plot of land through homesteading. Some say his home was a dugout while others claim it was simply a hole in the ground.

In 1887, Corbett was hired as assistant doorkeeper of the Kansas House of Representatives in Topeka. But a few days later, a judge declared him insane after he chased some men from the statehouse with his revolver. A year later, Corbett escaped from the Topeka Asylum for the Insane on horseback and was never heard from again.

In 1958, the local Boy Scout troop built a simple monument to him at the side of a rutted dirt road. It’s still standing, but just barely, and the hole has long since been filled in. But it’s still fun to stop and see the place where “Lincoln’s Avenger” once lived.

Editor’s note: Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this article misstated the date of the museum’s Victory Day celebration.

Joe Norris is a writer and former Wichita marketing executive. He can be reached at joe.norris47@gmail.com.