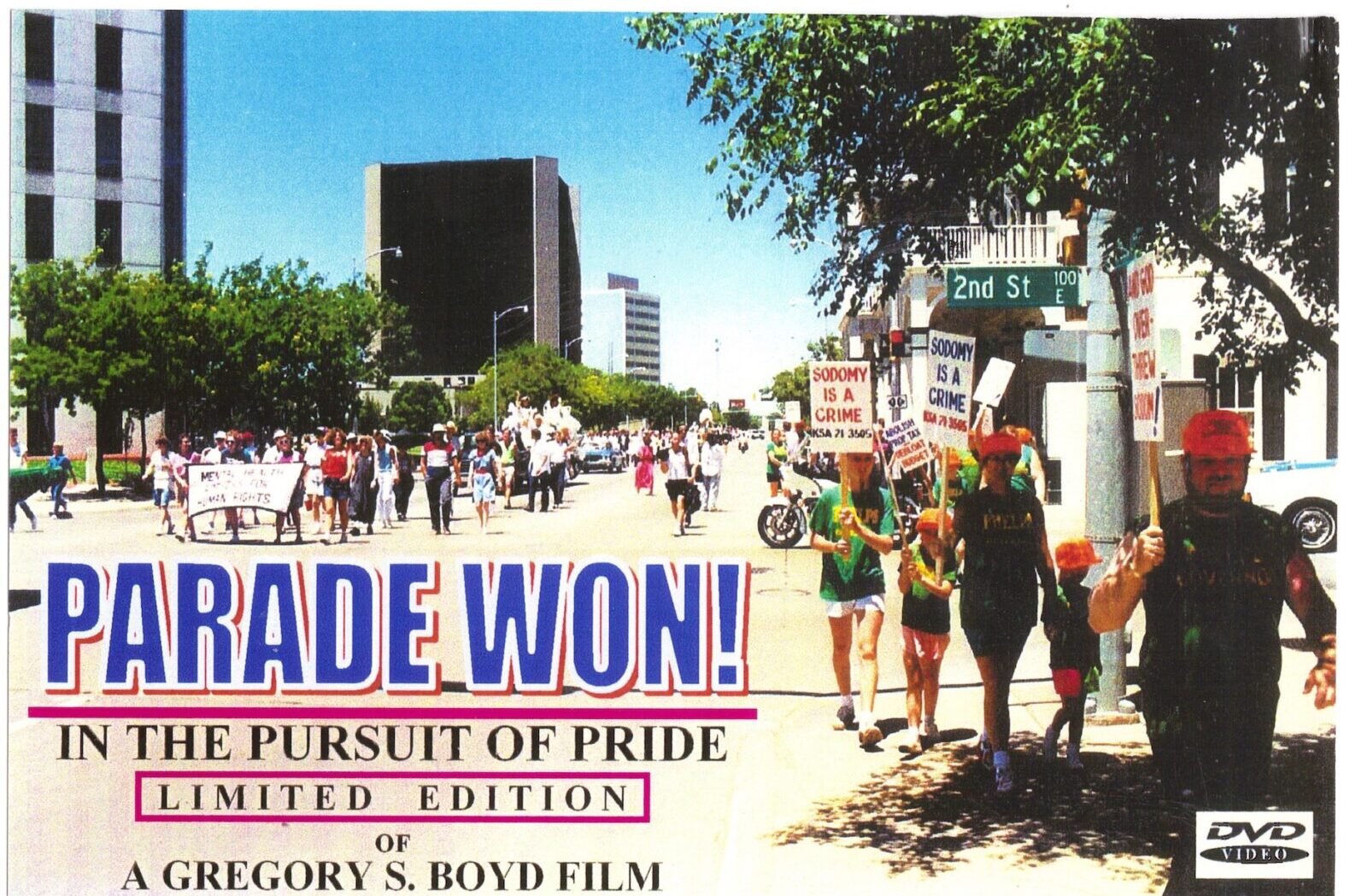

Click the DVD cover below to watch the documentary on YouTube.

Thirty years ago this month, Gregory Boyd filmed history in the making by documenting the genesis of Wichita’s first gay pride parade. He captured both sides of the story — organizers still fearful of anti-gay prejudice and violence and opponents led by the controversial Topeka figure Fred Phelps and his Westboro Baptist Church.

While parades in other cities had been filmed, Boyd said, “They never showed what it took to get the parade on the streets. … And I decided that’s the story I wanted to tell.”

To mark the anniversary — and because this year’s parade was canceled due to a ban on mass gatherings — Boyd is making his 82-minute documentary, “Parade Won! In the Pursuit of Pride,” available for free viewing on YouTube. Boyd, 66, calls himself a retired gay activist.

June also marks the 50th anniversary of the first gay pride march in U.S. history, held in 1970 to commemorate the one-year anniversary of what’s known as the Stonewall Riots. Patrons of the Stonewall Inn in New York City’s Greenwich Village had fought back against a raid on the gay bar.

One of the opening scenes of Boyd’s film features Phelps, pastor of Westboro Baptist Church in Topeka, unloading anti-gay signs from a van on May 10, 1990. Phelps had travelled to Wichita to protest a meeting of the parade planning committee, which was getting advice from parade organizers from other cities. It was one of Phelps’ first such protests. He became known for picketing various events, including U.S. military funerals. He claimed the soldiers’ deaths were part of God’s punishment for America’s tolerance of homosexuality.

At the time, Phelps was running for governor of Kansas and welcomed the chance to be interviewed, Boyd recalled. Years later, Boyd shared the footage with producers of the ABC News show “20/20,” which aired a segment by reporter John Stossel on the Westboro church.

Boyd was part of the inaugural parade’s planning committee until he became the designated documentarian. It was a story he wanted to share with others who were planning pride parades in their communities — to show them the conversations and arguments that happened behind the scenes.

His only other experience with a camera had come shooting 20 minutes of 8mm footage of a 1985 San Francisco parade for Hal Call, a decorated World War II veteran and an outspoken gay activist. Boyd, who lived in San Francisco between 1978 and 1988, described Call as one of his mentors.

In Wichita, Boyd shot more than 10 hours of footage between April and June 1990, using the style of cinema verité — in which subjects are shot with unscripted dialogue and action and natural lighting. That style worked particularly well when Boyd was granted unheard-of access to film Wichita gay bar owners and patrons. Since the bars were so dimly lit, the subjects’ faces could remain in half-shadow.

“No cameras had ever been allowed inside those bars before because those were still the days of random assaults, broken windshields and tires, and few people wanted to be seen on camera,” said Boyd.

The film includes reactions from the general public, airing what Boyd calls “really hateful” comments that had come into a KFH radio show when the parade was a featured topic.

The documentary was never meant to be shown commercially, Boyd said, so limited copies were initially made on VHS tapes. In 2004, Boyd converted the film to DVD and today has only one remaining copy.

Boyd said the film has only been released twice before: in 1992 when it was submitted to the San Diego Gay/Lesbian Film Festival and won Documentary of the Year, and in 2004 when he submitted the DVD to the Tallgrass Film Festival. It was rejected for “technical flaws,” Boyd said.

The original footage was donated to the Bruce McKinney Collection at the University of Kansas Spencer Library. McKinney, a well-known Wichita activist, had collected oral histories and other documentation of gay and lesbian life in Kansas. McKinney died in February.

It was McKinney who got Boyd involved in several early pivotal events within the Wichita gay-and-lesbian community. They, along with the Homophile Alliance of Sedgwick County, circulated petitions to get a gay rights City of Wichita ordinance on a special ballot that was narrowly passed in September 1977.

The original ordinance vote is why Wichita has a second pride event in September, Boyd explained.

Gay anti-discrimination ordinances were being passed throughout the country in the 1970s in such places as Cincinnati, Phoenix, Ann Arbor, Mich., and St. Paul, Minn., Boyd said. The ordinances were opposed by organizations such as Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority and Anita Bryant’s Save Our Children.

In Wichita, the repeal efforts were led by Baptist minister Rev. Ron Adrian and his Concerned Citizens for Community Standards, according to news articles from that time. Boyd participated in picketing one of Adrian’s rallies at Century II. The Wichita ordinance was overwhelmingly repealed in a special election in May 1978.

That vote caused “ripples all the way back to San Francisco,” Boyd said, noting that Harvey Milk, the first openly gay elected official in California, organized a protest around it.

Boyd, too, felt the effects of the repeal, deciding to leave Wichita for San Francisco where he met many of the movement’s “movers and shakers,” such as Call, who had been gay rights activists going back to the 1950s.

He remembers meeting Diane Feinstein, now a U.S. senator but at the time the San Francisco mayor, in the City Hall cafeteria. Boyd had joined Harry Britt, whom he was dating at the time, for lunch. Britt was Milk’s successor to the city’s Board of Supervisors after Milk was assassinated. Boyd also recalled seeing Nancy Pelosi handing out election flyers on a San Francisco street when she ran for her first Congressional election.

It wasn’t until he left for California that he confirmed to his parents and family what they had suspected: he was gay.

“My family had a ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ approach,” said Boyd, even though his name had appeared in some news stories about gay activism. His own recognition of his sexuality was a slow one, he said. He grew up in the Wichita area and graduated from Andover high school.

Boyd, who has three older siblings, said, “I was a little bit of an oddball.”

He was fascinated with news, history, art and theater. As a preteen, he read the Warren Commission report on President Kennedy’s assassination. As a teen, he devoured the writings of classic philosophers. After high school, he got involved with the local theater community. He started corresponding with well-known Hollywood makeup artist Dick Smith to get advice on doing stage makeup. (Boyd’s small collection of life masks includes two that Smith made when working with actors Marlon Brando and Buster Keaton.)

Boyd returned to Wichita in 1988 for a quieter pace of life and work in sales, he said.

After making the 1990 “Parade Won!” documentary, Boyd still dabbled in the theater, writing plays. Wichita Community Theatre staged his play on Truman Capote entering heaven, called “Angels Wanted, Halos Optional.” His one-act play “The Archive,” which was based on conversations he’d had with friends following the Oklahoma City bombing, won an award in a New York City competition and was produced “way off” Broadway, he said.

His activism had been motivated by that youthful ambition of “wanting to change the world,” Boyd said. He retired from activism in the local LGBTQ community more than a decade ago, he said.

“Being gay wasn’t something that consumed me. It was just a small part of me as a whole.”

Contact Amy Geiszler-Jones at algj64@sbcglobal.net.