Gerald McCoy was a boy when he saw Isaiah “Fireball” Jackson pitch in Wichita’s National Baseball Congress tournament. Jackson’s explosive fastball wasn’t the only remarkable thing about him. There was also the team he played for, made up of fellow prison inmates.

“My dad and I watched him lead the prison team to another tournament victory that night,” McCoy says. “I suppose everyone there was thinking the same thing: how could someone with so much potential fall the way he fell?”

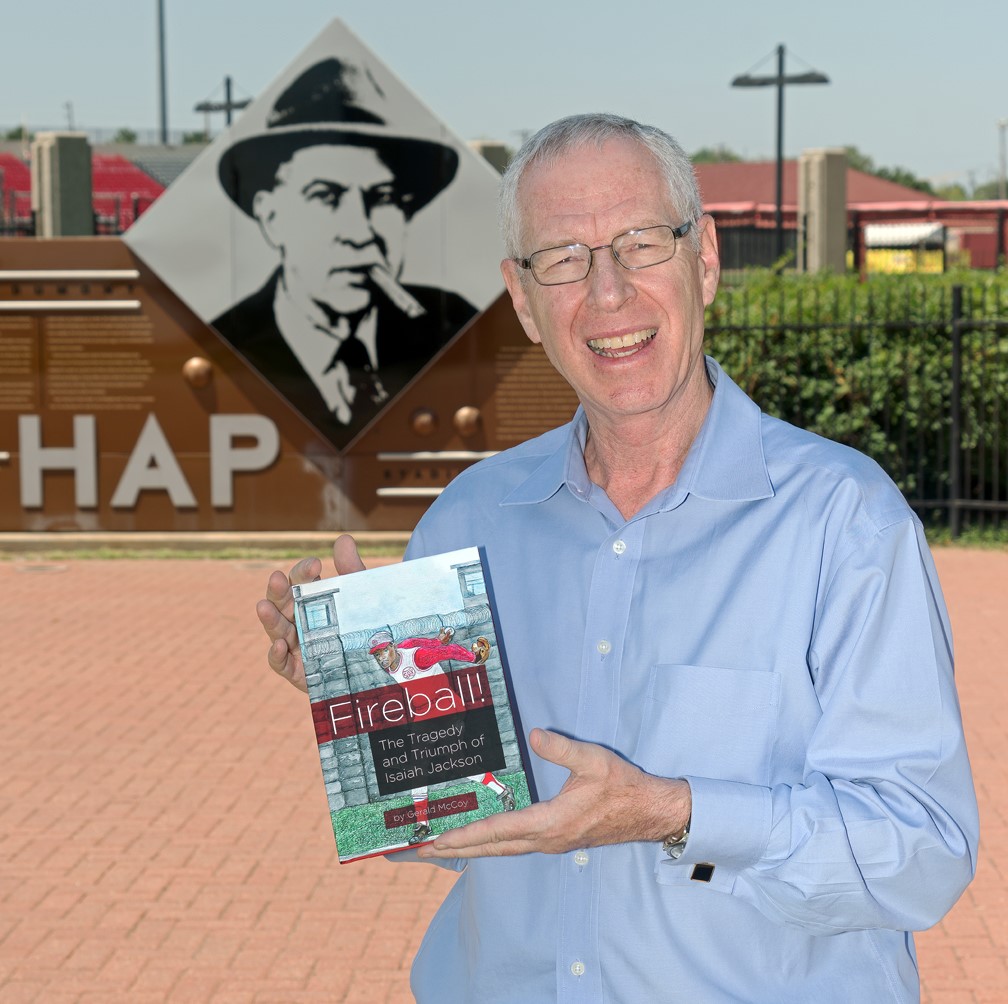

Decades later, McCoy has written a book answering that question and much more about Jackson’s troubled, fascinating life. Released Aug. 6, Fireball is available at Watermark Books and on Amazon.

Jackson, as McCoy writes, was three years old when his parents split up and abandoned their five children. The young Jacksons became wards of the state, sent to live in an orphanage in Atchison.

Isaiah ran away as soon as he was old enough. He was found and sent to the Boys Industrial School in Topeka. He escaped from there, too, was labeled an incorrigible and sent to the Kansas State Industrial Reformatory, even though he had committed no crime.

At 17, Jackson was released and moved to Kansas City to find his siblings. He had spent his entire life incarcerated, with no mentors and no guidance. He didn’t know how to drive a car, make a phone call or balance a checkbook.

Predictably, he got into trouble. Jackson and his brother were involved in a robbery and sentenced to 10 years in the state prison at Lansing. While there, he joined the prison baseball team and discovered a talent for pitching. Word of his blazing fastball spread, and it wasn’t long before Tom Demark, a scout for the Philadelphia Phillies, heard about it. Demark visited the prison, confirmed the rumors and decided to offer Jackson a contract. In the meantime, prison authorities gave him permission to coach Isaiah. Demark brought in Joe Presko, who had just retired from pitching for the Cardinals and Tigers, to help. They refined Jackson’s raw skills.

As soon as Isiah was released from prison, the Pittsburg Pirates signed and sent him to a minor league club in Reno to make his professional debut. But Jackson still lacked the life skills to make it outside prison. After a year, he left the team and moved in with his sister in Kansas City. He bought a pistol and robbed three cab drivers, netting $47 and another 10-year sentence at Lansing.

Hap Dumont was the owner of the National Baseball Congress in Wichita. A genius at promotion, Dumont knew that if he could arrange for a prison team featuring “Fireball” Jackson to play in the NBC it would draw big crowds, as Jackson’s legend had not died out. After extensive talks with officials at Lansing, Dumont got the go-ahead. And he was right — thousands turned out to watch Jackson.

When Jackson was finally released from Lansing, he proved unable once again to navigate the real world. He and his brother tried to hold up a café where a couple of off-duty police officers were dining. This time Jackson was sentenced to 30 years at the prison in Jefferson City.

There, Jackson developed a passion for painting. A baseball friend provided him with art supplies, and the convict gained a following for his eye-catching paintings. Released from Jefferson City after 20 years, he planned to support himself through his art, and this time he had mentors provided by the Mennonite Church. A woman in St. Louis who saw his paintings arranged for a one-man art show, but Jackson died before the show happened. It was a huge hit, lasting for six weeks.

In 1989, McCoy got the idea to write a book about Jackson’s life after reading an article on him in the Wichita Eagle. Two decades passed before he had the time to conduct extensive research. While in Missouri, he uncovered a trove of 15 of Jackson’s paintings, which his long-time friend Patrick Cantrell purchased for him. McCoy eventually plans to donate the majority of the paintings to a museum.

McCoy will speak about Jackson’s life at a program at Linwood Senior Center at 2 p.m. Sept. 10. There is no cost for senior center members and a $2 fee for nonmembers.

“How many people with talents like these fall through the cracks?” McCoy says. “I feel like this is my life mission – to tell his story. He was a remarkable man.”

Contact Debbi Elmore at

Debbi.Elmore2017@gmail.com