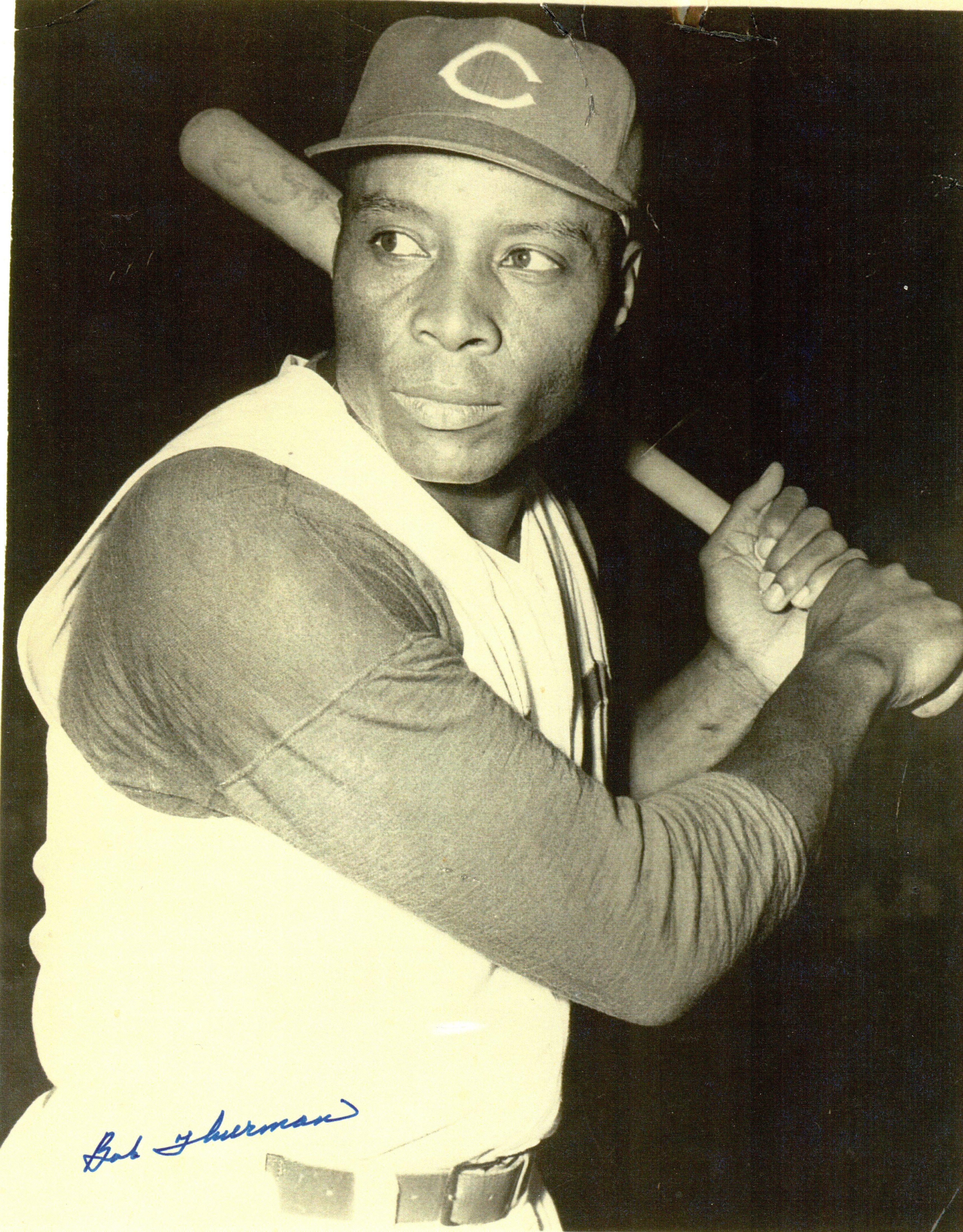

Bob Thurman’s name may not be as well known as those on other signs in McAdams Park. After all, playing fields there have been named for such all-time greats in their sports as Barry Sanders — the Heisman trophy winner and perennial all-pro running back — and Lynette Woodard, the first woman to join the Harlem Globetrotters.

Thurman was a star who played in an earlier era and didn’t actually begin his big league baseball career until 38, long after most players have retired.

The Wichita Park Board in late 2018 voted to rename the baseball diamonds at McAdams Park in Thurman’s honor, almost exactly 20 years after his 1998 death. It was a wise move.

Born in Wichita in 1917, Thurman played semipro baseball here until going into the Army. He fought in the Pacific Theater where he also played ball. There he caught the eye of the Homestead Grays, a powerhouse Negro National league team based in Pittsburgh, and Bob went there in 1945. He later joined the Kansas City Monarchs. But his brightest moment was with the Cincinnati Reds in 1955-1959.

Although held back for years by baseball’s color line, Thurman became the game’s best pinch hitter and probably the Reds’ most popular player. He was big—well above 6 feet tall and over 200 pounds—but a teammate once said he “has mercury in his shoes” he was so fast.

And he hit home runs, including three in one game. One of his nicknames was “Swish” because of his power-laden swing. He became the first big league player to hit a home run on his 40th birthday. His best batting average came in 1956 when he hit .295.

His Spanish language nickname, on the other hand, was El Mucaro, which means “the Owl.” That was because when he pitched in the Caribbean leagues he won almost all the games he pitched at night.

Like most Negro League players, economics forced him to play baseball year round. Thus, after his summers with the Grays and Monarchs he went to the Caribbean until spring training the next year. Some wondered if his 12-month playing schedule shortened his career. Doubtful. He was well past 40 when he retired.

His widow, Dorothy, told Wichita Eagle columnist Bob Lutz, “Just about everybody on those Negro League teams were stars. But people just didn’t realize it.”

Some did. With the Santurce Puerto Rico Crabbers, Bob was part of one of the best outfields in baseball history. He played right field. Willie Mays, reigning National League most valuable player, was in center. Another Hall of Famer, Roberto Clemente of the Pirates, was in left. Thurman was later inducted into the Puerto Rico Baseball Hall of Fame as well as the Kansas Hall.

Besides his play, Bob was a mentor for younger black players joining the Cincinnati team, helping them on the field and off.

Age seldom seemed to slow him. For his final season as a player, Bob signed with a minor league team in Charleston. In his last game, he pitched three scoreless innings in relief and had four hits in five tries.

Bob never left baseball. He came back to Wichita to be a scout, first for Minnesota, then Kansas City and finally the Major League Scouting Bureau. In that job he faced some of the same color barriers he had as a player. “At first they resented him,” Dorothy said. “But that didn’t matter because he knew what he could do and he could make friends.”

“He had a great sense of humor, He laughed a lot and he was a great evaluator of talent,” Owen Friend, a fellow scout and former major league player from Wichita, said. “He was one of the better scouts in the country when I worked with him.”

Bob took the bumps that went with being a pioneer black player and scout in stride. After his death from Alzheimer’s at the age of 81, Dorothy said her late husband “never seemed to regret not getting the chance sooner.”

“Baseball was always number one with him. It was something he liked to do, and he did it well.”

Contact Bob Rives at bprives@gmail.com.