Turns out Bob Bayer isn’t the only person interested in jailhouse artist Ernest Aspinwall. Since an article about Bayer and the creative criminal appeared in The Active Age in August 2022, he’s been contacted by several people who either knew Aspinwall, knew somebody who did or possessed one of his paintings.

Aspinwall made front-page news here and elsewhere during the 1940s and ’50s as a habitual criminal who was talented with a paint brush. Bayer’s wife, Dora, inherited 15 of Aspinwall’s paintings from her first husband, Lou Timmerman, a Wichita lawyer appointed to defend Aspinwall. The paintings now hang in Bayer’s home in north Riverside.

Aspinwall was charged with kidnapping a Wichita taxi driver in October 1940 but escaped from the Sedgwick County Jail and wasn’t returned to face trial here until a decade later. In the interim, he served time in the Missouri and Louisiana state penitentiaries. Convicted of the kidnapping, he was sentenced to life in the Kanas State Penitentiary at Lansing prison as a habitual criminal, but that was later commuted. A newspaper article reported that Aspinwall completed 30 works of art while awaiting trial here and several of works — including two 25-by-25 foot his murals — remain at Lansing, which is now open for historical tours. Bayer has visited the prison twice while researching Aspinwall.

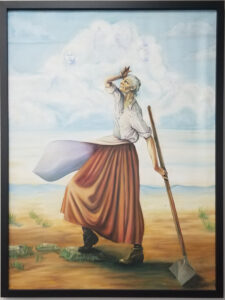

After reading The Active Age’s article online, Andrea Hathaway, collection services manager for the Olathe, Kan., public library, sent Bayer a photo of an Aspinwall painting that the library owns. The library calls it “Prairie Woman” although there’s no title on it.

As Bayer describes it, “It looks like this woman who is standing out on the prairie, and she’s got a hoe in her hand. And there’s nothing else in the picture to tell you where it was. She’s just standing out on the prairie, and she’s kind of windblown.”

Hathaway said she doesn’t know how the painting came into the library’s possession.

Bayer obtained Aspinwall’s portrait of the chaplain at the Missouri state penitentiary — where Aspinwall served time — from a resident of the St. Louis area who’d also seen the original article. “That was the only portrait that he did,” Bayer said.

He also heard from former Wichitan Bruce Underwood, whose father, Jim, was chief of detectives for the Sedgwick County Sheriff’s Office when Aspinwall was brought back to stand trial.

“I think my dad was the one who put him back in jail,” Underwood said. “He told dad he was an artist and asked if he could get some supplies. My dad did get him a bunch of supplies.”

In return, Aspinwall gave him three paintings. One was called “The Chalice Diablo.”

“Aspinwall could be kind of dark,” Underwood said. “It was a silver goblet with a man immersed in it, screaming in agony. I guess if you looked at the pupils of his eyes with a magnifying glass, they were inverted crucifixes, so my mother wouldn’t let that in the house. I don’t know whatever happened to it.”

The third, painted on silk, portrayed Aladdin and a genie coming out of a lamp. Underwood had it framed after his father’s death.

“It’s a pretty large piece, like 42 inches wide and 32 inches high. It’s a really nice painting. It hangs above my bar right now.”

Bayer also tracked down the son of a parole officer who’d been mentioned in an old Kansas City Star article that ran with a photograph of one of Aspinwall’s paintings. “It took about a year but we finally got together,” Bayer said. “I told him we had about 15 paintings that Aspinwall had done and he said, ‘Do you have room for one more?’ And he gave me that painting.”

In that work, Aspinwall copied Picasso’s well-known Don Quixote sketch.

Bayer also heard from Albuquerque resident Harry Klemfuss, who painted a colorful word picture of the artist’s time in New Mexico following his release from Lansing.

“I spent a lot of time with Ernie Aspinwall in Albuquerque over a three-month period in early 1973,” Klemfuss wrote in an email. “I sublet a room with kitchen privileges from a group of Scientologists trying to start a drug abuse treatment center called Narconon. Ernie showed up a week or so later from Phoenix; he apparently knew a female Scientologist there, and it is my understanding that the Albuquerque group gave him a free room and offered to train him to use Scientology procedures for treatment.

“He was a small, thin old man, soft-spoken with a gentle manner, but even before I knew of his past I could sense that he was tough on the inside. I got occasional temp jobs when I could to pay for food and rent. He worked on commission selling cactus plants in Albuquerque’s Old Town. Neither of us earned much.

Making a “splash” in his black cape and earring, Aspinall “occasionally would score some free drinks for us” in local bars.

“He did not sell many cacti and he lost that gig, but he claimed a nice spot on the Old Town Plaza and did charcoal portraits of tourists. When I was not working I served as a shill; he must have done 50 or 60 charcoal portraits of me over three months. I gave one to my parents that they hung in the living room. No idea where it is now.”

Klemfus ended his email by saying he “thought of him often since then.”

Slight and darkly handsome in his youth, Aspinwall spoke with an upper-crust Boston accent and reportedly came from one of New England’s oldest families. The last apparent mention of him in the media came in 1977, when Aspinwall was reported by United Press International to be working as a street artist and art therapist for a San Francisco mental health center. He was described as a “rather colorful figure, in fancy clothes and white shoulder-length hair. The image is topped off by Matt, his Afghan hound.”

Bayer is in the process of writing a book about the artist. Asked what interests him about Aspinwall, he said, “Well, just the the subject matter of all these paintings that I have. Aspinwall was in a real — you might call it a weird state of mind — when he was in the jail here in Wichita, because he knew he was facing long-term prison. He had already had four major crime convictions, he was one above the limit where he could go to jail for the rest of his life.”

Bob Bayer may be contacted through The Active Age by emailing joe@theactiveage.com.