By Mary Clarkin

Micky Maddux encounters the homeless three to 10 times a day. She does not live or work in a shelter or sleep on a sidewalk. She’s the owner of an art gallery in Wichita’s Old Town Square.

She’s cleaned their urine and feces off her gallery front in the morning, been accosted and heard their shouting.

“Sometimes it’s not always aggressive,” Maddux said. “Sometimes it’s heartbreaking.”

As she spoke, a man slept on the sideewalk in the shadow of a pillar yards away from the entrance to her gallery.

Maddux, who moved back from Florida and opened the gallery in May, previously donated pieces of art to raise money to help people in need. She said if there was anything she could do, she would, but she doesn’t know the answer.

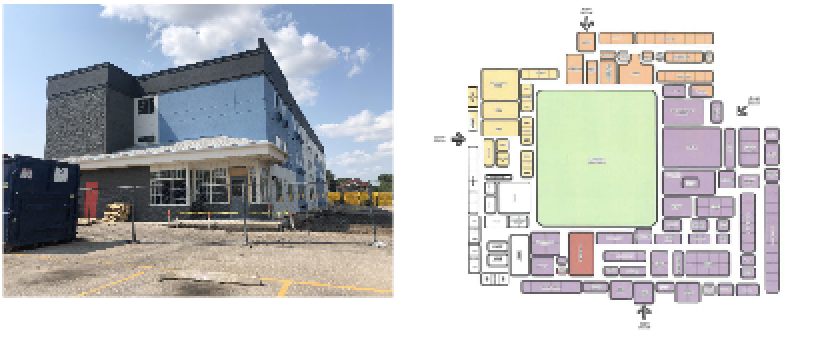

The former 316 Hotel on north Broadway, above left, will soon provide housing for homeless people and those in danger of becoming so. A proposed new COMCARE Crisis center, right, would include a large green space surrounded by a substance abuse center, crisis observation unit and more.

‘This is a disaster’

Homelessness, mental illness and substance abuse are often intertwined, with quality-of-life ramifications for the broader community.

The annual Point-In-Time homeless count in January 2020 found roughly 2,500 people in Kansas living in shelters or on the streets, up 16 percent from 2007. The category of “severely mentally ill” was the largest subset within Kansas’ homeless, bigger, for example, than veterans or unaccompanied youths, according to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Chronic substance abuse was the second-biggest category.

Sedgwick County’s annual homeless count tends to hover under 600.

The Mental Health and Substance Abuse Coalition of Sedgwick County was formed in 2019, uniting law enforcement, social and medical services, government, business, and non-profit agency leaders. Armed with a strategic plan for 2020-2025 to combat homelessness, mental illness and substance abuse, the coalition’s momentum ran headlong into the COVID-19 pandemic and shutdown.

Meanwhile, the problems grew worse.

“This is a disaster as far as what’s happening in our community,” said coalition member and Intrust Bank executive Gary Schmitt at a June session of the Sedgwick County Commission. He had seen a dozen people sleeping on the ground downtown that day.

Sedgwick County Commissioner Lacey Cruse, also involved in the coalition, saw even more sleeping outside when she drove down Topeka Avenue one Sunday.

“Some of these folks are getting very aggressive,” Cruse said. “Just the other day at Central and Broadway, I had a man almost open my door as I was driving down the street.”

Deann Smith, executive director of the Open Door shelter/food/clothing program, and Jan Haberly, director of The Lord’s Diner, have observed trends among the homeless.

“I can tell you within the last five, seven years, that it’s progressively gotten worse as far as the behavioral issues,” Smith said. She points to mental health and substance abuse and the need for access to treatment.

“I think before there just weren’t so many struggling with mental illness,” Haberly said. “I think that the treatment isn’t as readily available, but then I think people are trying to treat themselves.”

Crime in the central area

The Wichita Police Department started the H.O.T. (Homeless Outreach Team) in 2011 in an attempt to help the homeless rather than criminalize them.

Officer Nate Schwiethale, who promoted the idea, asked for four officers for the H.O.T. unit in the beginning but three were allocated under a prior police chief. When the unit began to fall behind on camping complaints, current chief Gordon Ramsay added a fourth officer. Schwiethale considers the unit appropriately staffed and said it is “most always” on top of camping and vagrancy complaints.

Department policy is to give wide latitude to violators, as can be seen in Policy 503, which spells out how the city’s anti-camping ordinance should be interpreted. Section 5.20.010 of the city code prohibits camping on public property without a permit as a “public health and safety hazard which adversely impacts commercial areas and neighborhoods.” Violations are punishable by a fine of up to $500 and 30 days in jail. Policy 503, however, directs officers to give offenders a 48-hour warning period, plus a referral to an appropriate social service agency. At the end of that warning period, officers are instructed to try to find a shelter for the offender. If one can’t be found, “no criminal case will be made for the incident and the individual is left alone.”

Officers may order a clean-up of the camping area and place items such as tents and sleeping bags into evidence. But another section states: “Officers are expected to use discretion in accordance with 5.20.010, to balance the needs of the individual with the needs of the community on a case-by-case basis.”

When a homeless person is suffering a mental health crisis, a new program called ICT-1 partners multiple parties — a paramedic, police officer and social worker — to stabilize someone in a mental health crisis. That will be the model of the future, Ramsay has said.

Schwiethale rejects suggestions that the city’s dramatic renovation of Naftzger Park, approved in 2017, pushed the homeless from what had been a longtime hangout into other sections of the city’s central core, even though critics predicted that it would do just that. In his experience, only about five to 10 homeless people hung out at the park at a time, Shwiethale said.

Mental illness contributes to more serious crime in central Wichita, too — allegedly including a recent murder.

On May 5, William H. Robinson II, a security guard at the QuikTrip near Broadway and Murdock who was known for helping homeless people who frequent the store, was shot in the face and later died. Laroy M. West, 41, was charged with second-degree murder, four counts of aggravated assault, and two counts of criminal possession of a weapon by a convicted felon. Robinson had escorted West out of the store for being loud and disruptive. On March 28, West allegedly threatened two men with a gun outside of a restaurant a few blocks north of where Robinson was shot.

In a court petition for a mental evaluation of West to determine if he is competent to stand trial, West’s attorney, Jeremy Koop, wrote that West “has had a history of mental health issues and is currently exhibiting behaviors consistent with significant mental illness.” The results of the evaluation are pending.

Less inpatient treatment

At least two developments related to the treatment of mental illness may be contributing to what some see as a rise in homelessness and associated problems here.

In the 1990s, the state of Kansas adopted a new approach toward mental health treatment. It reduced state mental hospital beds and shifted to a community mental health approach.

“We said the money would follow the people and obviously, that didn’t happen,” said Rep. Brenda Landwehr, R-Wichita.

Over about three decades, the number of inpatient behavioral health beds in Wichita dropped from about 600 to 101. All 101 beds are at Ascension Via Christi St. Joseph, near Harry and Hillside, that hospital’s president, Robyn Chadwick, told Sedgwick County commissioners in June.

A mix of for-profit and not-for-profit providers previously offered behavioral health inpatient beds, but abuses in the system spurred more regulations, and it didn’t pay to offer those services.

Patients arriving at the emergency room at St. Joseph who are assessed as needing a behavioral health bed can wait as long as two days in the emergency department before a unit bed is open.

Patients are requiring longer stays in the hospital. The cost of uncompensated care runs into the millions.

“We’re seeing a much sicker population and more of them,” Chadwick told commissioners.

The level of violence is up in the hospital. A day when a nurse or a doctor isn’t assaulted is unusual, Chadwick said.

In spring 2021, Chadwick received a heads-up phone call from Sedgwick County’s COMCARE that a prisoner being discharged from El Dorado Correctional Facility needed a bed at the state mental hospital in Osawatomie, but it didn’t have a bed. The plan the state devised was to transfer the man to St. Joseph’s ER until Osawatomie had a bed, Chadwick told county commissioners.

“It didn’t seem to me that a not-for-profit, Catholic, private hospital really needed to be part of the state’s discharge plan,” she said, but St. Joseph took the man.

If St. Joseph hadn’t taken the discharged prisoner, he most likely would have shown up at Open Door’s day shelter, and Open Door would have been searching for a bed for the man until he could get into Osawatomie, Smith said.

A new approach

In 2014, Congress funded a program aimed at bolstering community mental health centers. Kansas wasn’t among the eight initial states to take part, but as the program’s success became clear, the federal government allowed individual centers to apply. One in Kansas did.

Four County Mental Health Center, serving Chautauqua, Cowley, Elk, Montgomery and Wilson counties, took advantage of the Excellence in Mental Health Act when centers could apply. Four County is in the closing months of a two-year grant to develop the types of programs to be a Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic at the federal level. That CCBHC designation brings an improved reimbursement method and a new approach toward treatment.

Four County “wraps” all of its services around the person to get them stabilized, according to Greg Hennen, executive director.

“We’ve had fantastic results in getting people moved from homeless to securely housed,” he said. “If they’re sleeping under a bridge, we’re going under a bridge,” he said. “‘Hey, remember us, this is what we have to offer,’” a team member will say. They focus on those individuals intently during those first weeks of contact, he said.

The 2020 Kansas Legislature’s Special Committee on Kansas Mental Health Modernization and Reform, chaired by Landwehr, brought 30 to 35 experts in the field to work with legislators. The result was sweeping health legislation in 2021 that calls for all community mental health centers in Kansas to become, over three years, a CCBHC.

“We’re going to learn from any mistake that they made,” Landwehr said of Four County.

The reimbursement rate for CCBHCs is based on the cost to deliver services, instead of a fixed cost that may or may not cover costs. The new higher reimbursement as community mental health centers become CCBHCs “means that they could pay better wages to hire more employees and keep those employees,” Landwehr said.

It will bring “the biggest change in mental health care in Kansas in the last 30 years,” Landwehr said, and the 2020 work of the Special Committee was just the start, she said.

Pandemic plus

Pandemic relief aid from the federal government enabled greater spending to counter homelessness.

.Last year, the city bought the former 316 Hotel on North Broadway and announced plans to convert it into a 56-unit complex for the homeless and those vulnerable to becoming so, with on-site social services. It will be owned and operated by HumanKind Ministries. The work had not been finished as of July, but Mayor Brandon Whipple believes it will be a game changer.

“When it comes to homelessness, we’ve been using this older model,” Whipple said. Night shelters are closed during the day with the expectation people spend the day finding a job. “But homelessness is usually the outcome of something bigger,” he said.

There’s also a proposal for a new Sedgwick County COMCARE Community Crisis Center that would be larger than the current center at 635 N. Main. No site has been selected, but it likely would be downtown and anchor a campus where services would be available for the homeless and those struggling with mental illness and substance abuse. Tools to help people find a job or get an education also would be offered.

A full-time executive director to help shepherd the campus idea into existence likely will be hired and in place this fall.

The 2021 American Rescue Plan Act will bring slightly over $100 million to Sedgwick County and about $72.4 million to the city of Wichita. Brenda Dietzman, a consultant and project manager on the coalition’s strategic plan, thinks those funds will play a big role in moving forward with a new community crisis center campus.

Organizers also envision a virtual campus. A database will provide patient information that providers can access; an online dashboard will help people in need or their families learn about services.

San Antonio has created a centralized campus that is expected to serve as one model for Wichita.

“We don’t have to reinvent the wheel, but we do need to invent the wheel that’s right for Wichita,” said Open Door’s Smith.

Just building another homeless shelter is not necessarily helping people move forward. It has to be more than that, she said.

“I’m a strong believer that we’re only as strong as a community as those who are struggling the most,” Smith said. “We all belong to somebody,” she said. “For me, I don’t believe anybody’s a throwaway.”

Robin’s story

The concentration of social service providers in central Wichita contributes to the larger number of homeless congregating there. Would adding more services attract even more homeless? The answer is: They are already coming.

Fifty-four-year-old Robin —she preferred not to give her last name – sat outside near Central and Topeka one June afternoon. For about a half-month, a bunk bed inside HumanKind Ministries’ shelter had been her refuge. She was grateful for the night shelter, and for the nearby day shelter operated by Open Door, and to the Lord, she said.

She also appreciated the Woodson County Sheriff Department, which brought her to Wichita.

“Pretty accurate,” Woodson County Sheriff Jeff McCullough said of Robin’s account of the odyssey that brought her here.

Robin, who once lived in a vehicle in a Walmart parking lot in another state, said her husband died of sepsis in a veterans’ hospital in Georgia in late 2020. She found herself in Allen County in southeast Kansas in need of housing. Law enforcement there gave her a ride to neighboring Woodson County, to get her closer to Greenwood County where a relative lived. But it turned out she wasn’t able to stay at the relative’s home, so “we’re stuck with this person until we get her to a place of safety,” McCullough said.

Woodson County has no homeless shelters. There were no criminal charges against Robin, and jail’s not the place for the homeless, he said.

“We started just reaching out” to find a shelter bed, McCullough said. There was possibly one in Topeka. HumanKind Ministries definitely had a bed. Was there any way Robin could get to Wichita?

“I said we will take her,” McCullough said. The roundtrip is nearly 200 miles.

“This time of year,” McCullough said, “we start having homeless come through our county every day.”

Robin hoped to find a job. On her to-do list was obtaining a Kansas I.D. and getting a phone. She also wants to use COMCARE’s counseling services. Because of COVID-19 restrictions, she wasn’t allowed in the hospital when her husband died, she said. “I never went through grief counseling.”

This article was produced as part of the Wichita Journalism Collaborative , which includes The Active Age and six other organizations. The collaborative is examining mental illness in our community for more information, visit wichitajournalism.com.