Society wife-turned-gossip columnist Zoe Anderson Norris stirred up early Wichita with her sharp pen. As it turns out, she was just getting started.

Norris went on to become one of the most prolific writers of her time as well as a colorful New York City personality known as the “Queen of Bohemia.” Now, the author of a forthcoming biography of Norris wants to rescue her from the relative obscurity into which she fell after her death in 1914.

“I’m fueled by the fact that she constantly wrote about how women’s stories don’t get told,” Eve Kahn said. “She was misquoted and misportrayed in the press, and she ranted about it.”

Kahn’s book about Norris has been accepted by an academic press and is expected to be published next year. In March, Kahn is staging an exhibit and will speak about Norris at the Grolier Club in Manhattan, the country’s oldest and largest society for bibliophiles and graphic arts enthusiasts.

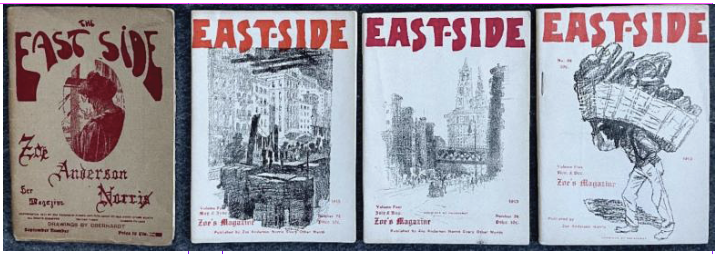

Kahn is a former antiques columnist for The New York Times who’s also written about art, architecture and design for it and other publications. She first learned about Norris in 2018 when she visited the home of a New Jersey physician and noted collector of American periodicals. He handed Kahn a bound volume of a magazine called The East Side, which she found was full of sympathetic sketches of New York’s poor immigrant population in the early 1900s — “incredibly rare for the time,” Kahn said.

Intrigued, she wanted to learn more about Norris, who published the magazine and wrote virtually everything in it.

“I asked myself, ‘What’s been written about her?’” Kahn said. “The answer was almost nothing. There was one article about how she had predicted her death in 1914, which was the least of her accomplishments.”

Once she started researching Norris in earnest, Kahn discovered a woman who seemed to have lived several lives in the span of one relatively short one.

Born into a well-connected but impoverished family in Kentucky, Norris first came to Kansas with her brothers and widowed mother in the 1870s, homesteading near Ellsworth. She returned to Kentucky to attend college, then married and settled in Wichita by 1887.

Her husband, Spencer Norris, opened a specialty grocery store at Main and Douglas, while the family lived on fashionable North Market. The store was known for everything from its milkshakes to fruit and cigars.

Then, as Kahn puts it: “He cheats on her, and she busies herself throwing parties. She simply becomes a prominent society hostess.”

Actually, Norris busied herself in various artistic endeavors, as Kahn’s research shows. She and her daughter, Clarence, performed in piano concerts at what was then Garfield (now Friends) University, taught art at Lewis Academy on North Market and, with other members of the local ceramics club, exhibited painted china at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago.

Norris threw parties for the Conversazione Club — formed to cultivate “refined and interesting conversation” — and was known for bedecking her home with flowers while entertaining members of the Levy, Eaton, Murdock and other prominent local families.

The Norrises divorced in 1898 — the house on Market was sold to cover Spencer’s debts — and Zoe began writing a gossip column for Marshall Murdock’s Wichita Eagle in the early 1890s under a pseudonym, Nancy Yanks.

Kahn called it both vicious and hilarious.

“She slammed everybody. Musicians, attempted writers, prohibitions, cheating men, all the different censors, all the people who were trying to beat back vice in Wichita.”

They appear to the first published words of many hundreds of thousands that would come from her.

“There’s no sign of her having written a word until she started contributing this gossip column to the Eagle,” Kahn said. “Where she got the idea, I don’t know.”

Norris also began writing fiction and journalism for other publications, apparently doing well enough at it to take her daughter, Clarence, on a year-long trip to Europe. They then settled in New York City, where Norris’ prodigious production seemed only to increase.

Norris wrote fiction and poetry for dozens of publications such as Frank Leslie’s Monthly, Harper’s Weekly and Munsey’s, while her journalism appeared in the Times and other New York newspapers.

All three of Norris’ novels have strong Wichita or Kansas connections. “The Color of His Soul,” published in 1902, portrays a hypocritical socialist orator whose character was based on Courtenay Lemon, whose family had lived in Wichita at the same time as Norris. The book was suppressed after Lemon “literally came forward and said ‘I’m the role model for this horrible character,’” Kahn said.

“I can tell you that Zoe knew the Lemons well and her version of the story is that Courtenay Lemon agreed to be portrayed in her novel but then withdrew support when she refused to share royalties,” Kahn said.

Her next book, “The Quest of Polly Locke,” followed a young Kansas woman as she toured Europe alone in search of love.

Her last book, “The Way of the Wind,” which appeared in 1911, is a tragedy about a farmer who owns valuable property at the future site of Wichita, apparently inspired by the city’s boom-and-bust days that Norris witnessed first hand.

Norris published The East Side every other month from 1909-1914, documenting poverty, corruption, sexism and more, sometimes going undercover for stories and depleting her savings to keep the publication going. “She dressed as an immigrant musician on the street to see how police would treat her, how philanthropists would treat her,” Kahn said. When not working, she founded and partied with a group of fellow eccentrics called the Ragged Edge Klub, earning her royal nickname. She died in 1914, at age 53, shortly after writing about a dream she’d had in which her dead mother foretold Zoe’s death.

Kahn, who visited Wichita in 2021, credits Jami Frazier Tracy, curator of the Wichita-Sedgwick County Historical Museum, and local historian Jim Mason for making the research mission a success. “Jim Mason, he drove me around patiently for days.” Among other sites, she visited Murdock’s house at the Old Cowtown Museum, the historic former county courthouse where Norris’ divorce was granted and family graves at Maple Grove Cemetery. Kahn said she doesn’t know of any relatives of Norris living in the area today.

Although newspapers noted Norris’ death, Kahn believes she’s not well known today because of her relatively early death and the fact that her personal papers were, characteristically, in disarray. After attempting to read “everything written by her and everything written about her,” Kahn offers this description:

“She was high-keyed emotionally. She had good days and bad days, and she writes vividly about her mood swings. She was impractical. She called herself a lazy Southerner. By the time she introduced The East Side, which focused on desperate poverty, she was at the ragged edge of poverty herself.”

She apparently only visited Wichita once after leaving and had a love-hate relationship with the place where she got her start writing.

“She never stopped writing about Kansas, either complaining about it or remembering it.”

Contact Joe Stumpe at

Joe@theactiveage.com